INKEY$ and his 8 legs

Back in the 80s, kids who had a ZX Spectrum or ZX-81 actually learned to program before they could read and write. This doesn’t sound very believable, but it’s the main reason Eben Upton and co. created the Raspberry Pi, so I thought I’d say something about how that worked.

Budget computing

The Speccy’s crude operating system was a BASIC command line interpreter, complimented by a simple line editor. When you switched the thing on, the machine’s cheap capacitors whistled with a high pitched coil whine inaudible to adults, the screen flashed black as the memory’s graphics region was reset, and about a second later you were presented with Sinclair BASIC’s operating system:

Well, to be more accurate, it wasn’t when you switched it on, it was when you plugged it in. Luxuries like an on/off switch had no place in Sinclair’s quest for affordable home computing.

A power button wasn’t the only missing feature - budget home computers of the 80s outsourced their peripherals to existing consumer electronics. Cathode ray tube monitors were expensive, and ones with digital inputs had no other function. So, like gaming machines before it in the 70’s, the Spectrum came with an RF modulator. You’d connect it to the family TV’s aerial port with a coaxial cable and tune it in the best you could.

More expensive computers had disk drives, but on machines like the Spectrum, Commodore 64 and Amstrad CPC series, games were stored on audio cassette tapes. You played into the MIC port with cables connected to a radio cassette player, directly into the headphone/mic port, using a splitter cable to separate the mono MIC and EAR channels.

A conflict of interest

The main reason to buy a home computer was to play games, but engineers built home computers to bring the glory of computing into the home.

So, gaming was both the killer app and also a grubby, degenerate, secondary

function, kind of like porn was to the early Internet. And like that conflict

caused Flash Player to dominate the web for a decade, this one led to a user

experience that few would stand for today: To load a game, you’d instruct the

thing to do the loading; you had to enter the LOAD keyword into the CLI.

This sounds simple enough, but the ZX Spectrum’s budget constraints came with quirks, making this process not only famously awkward but also different to every other home computer.

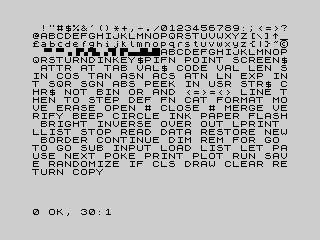

The ZX character set

Short on RAM, CPU and long on ideas, the boffins at Nine Tiles decided that

their BASIC interpreter could do without the text part of their lexical parser

and instead dealt in tokens. So they assigned all possible functions to an

extended character set. Characters 0xA5 to 0xFF became entire words rather

than a single character, and to input them, the text cursor switched between

modes depending on context. A flashing K for keyword input, an L for

letters and so on. This acted as extended forms of the SHIFT key, not quite

as many as modern Macs, but enough to be just as confusing.

Here’s the output of a BASIC program that prints the set, taken from Wikipedia:

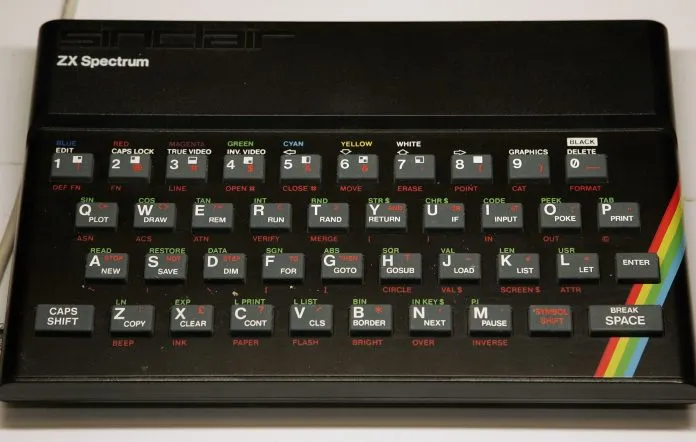

To help with the task of input, the budget rubber keyboard had all the keywords

printed on it. So, getting back to the loading ritual, to load a game you’d find

and squidge down the key with the word LOAD on it.

If you didn’t spot it, LOAD was conveniently located on the J key. And nex

we just tap ENTER, right?

Nope! You also had to pass the name of the program you wanted to load. Not that

anyone actually used this name filter, tapes were slow and filtering by name

would mean sitting for 4 minutes listening to some other program’s memory dump.

I like to think it was a psyop by Steve Vickers to teach programming by stealth.

Maybe it wasn’t, but it certainly worked that way. Plus, unlike the LOAD

keyword, there were other commands that had optional string parameters. It was

an act of spite: this thing did’t want you to load games.

If, like everyone, you didn’t care about the program’s name, then you just

entered an empty string: a pair of empty double quotes. These, even more

conveniently than LOAD, were inserted by holding down the aptly named

SYMBOL SHIFT and squishing the P key twice. Then you finally pressed ENTER

and clunked down the play mechanism on your cassette player.

If the tape wasn’t too worn, too stretched and hadn’t got too hot or too damp, it wasn’t wound too tight, and wasn’t an 8th generation copy from a chain of people’s mums’ dual cassette decks (the ones with Hi-Speed Dubbing) it might load. But only if the impatient kids didn’t shock the tape heads by jumping about the room, or squabbling too roughly. If you passed the test of patience then your game would be ready to play in 3 to 4 minutes.

That 4 minutes felt like a whole day.

GOTO 10

The looming 4 minute eternity made the flashing K cursor an open invitation

to play with the other keys. If you pressed P it typed PRINT, and if you put

some letters between the quotes after it then it’d whatever you wrote to the

screen (in CAPS, because the CAPS SHIFT key was for the exotic and alien

lower-case letters, a rare sight on the device).

If you wanted some real fun, you could put a number before the keyword and it’d

get saved to one of the 9,999 available line numbers instead of just running it.

Then you’d run them in line-order with the R key, or GOTO one of them with the

G key. So we did.

10 PRINT "HELLO"

20 GOTO 10

And that’s how I became an illiterate programmer. I couldn’t spell LOAD or

CLEAR on my own at the age of 6, but I could see what colour there were and

that they were different to the other allowed keywords. BEEP is written as

bip when you’re 6, but you can read BEEP and it made music if you gave it

some numbers.

This is how Sir Clive Sinclair earned his knighthood. He created a generation of programmers who could code before they could write. Ones who went on to ⏯ transform the world.

An imaginary friend

If you wanted to take a key from the keyboard without waiting for someone to

ENTER it, which you had to do if you wanted to move a ▄█▄ around the bottom

of the screen, you’d use the INKEY$ keyword to save it to a variable. Or a

“little box”. INput KEY, dollar meaning it returns a string.

If you’re 6 years old, don’t know what “input” means and call your keys

“buttons” then INKEY$ conjures up images of a friendly octopus with his arms

all over your buttons catching the ones you press. Legs actually, because only

humans have arms.

To me, INKEY$ is a cartoon octopus printed on 4 inches of thin card. One with

SEE INLAY FOR DETAILS written along the side.

Ah.. memories!